However, what lingered was a feeling that the protests were not only against the treaty, but against the government’s increasing control over the body

The police were an important arm of the metropolitan government’s beautification campaign, which involved legislation against the illegal dumping of trash, obstruction of traffic, illegal construction, and urination in the street. As Yoshikuni says, this goal to create a clean city was “part and parcel of Japan’s attempt in the 1960s to construct a more modern, rational space in Tokyo”

One of the students who was injured in a confrontation with the police during the antitreaty protests expressed his desire that the wound last the rest of his life in order to inscribe his political experiences as a physical scar.

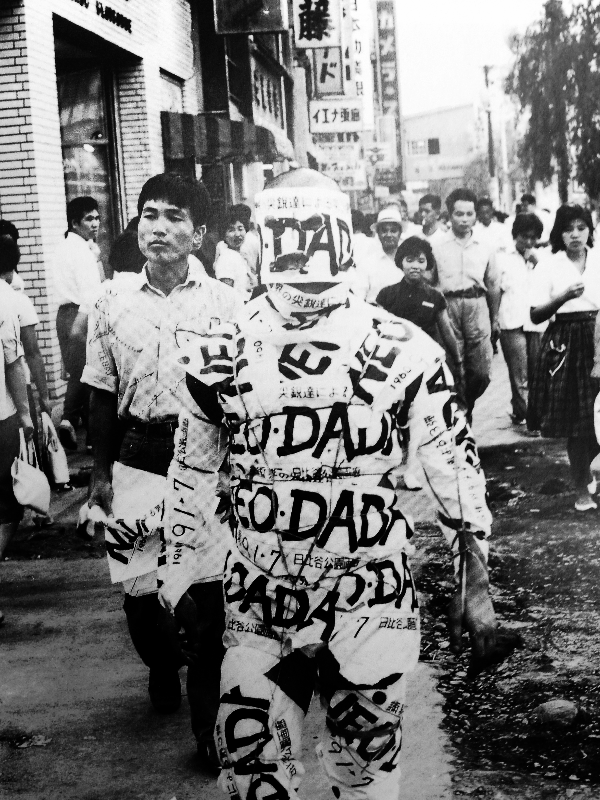

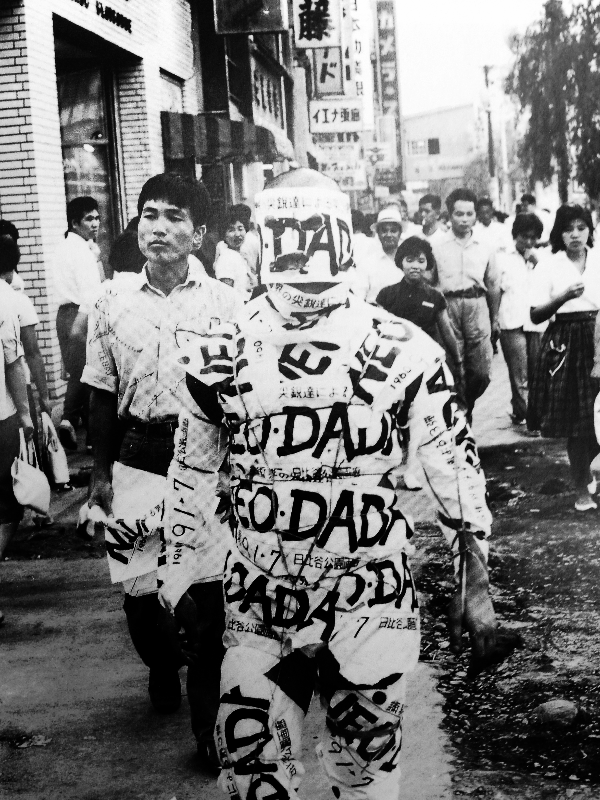

Suspended between art and guerrilla warfare, their text echoed the inflammatory rhetoric of radical movements and their artistic strategies mimicked the aggressive tactics of the police and municipal government

As the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), led by Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, was in the midst of negotiating a revision to the original 1951 United StatesJapan Security Treaty, a wide range of citizens took to the streets of Tokyo and formed opposition rallies.

Day after day tens of thousandsfrom high school students to the elderlysurrounded the Diet building and the American Embassy (Igarashi 2000). On June 4th, around 5.6 million people participated in a general strike, shutting down thousands of stores as well as public transportation.

By colliding with a growing sense of nationalism in Japan, the rallies allowed the Japanese people to express emotions which had long been repressed under a foundational narrative imposed on them by the State.

Violence of the Body

Yet the State was able to pacify the protesters with aggressive tactics and physical confrontation. Many were injured, several students were killed, and eventually the United StatesJapan Security Treaty was automatically ratified without deliberation.

The antiSecurity Treaty struggle brought tens of thousands of protestors day after day to the Diet building to show their opposition to what they saw as Western dominance and authoritarian Japanese politics. The treaty was ratified, and a great number of protesters, mostly students, were injured in confrontations with the police.

Many saw the antirevision movement as an opportunity to address a kind of authoritarian democratic order that that existed even before the war. At the same time, the protesters opposed the hegemony of U.S. military power in East Asia.

In the years leading up to the 1964 Olympics, the Japanese government implemented various policies that sought to regulate, and modernize, the body in what can be considered everyday spaces of the city. The Women’s Bureau in the Tokyo Metropolitan Welfare Office initiated a campaign to protect Japanese women from the romantic and sexual impulses of foreign men. Popular culture magazines also began to encourage the chastity of Japanese females, which formed part of a larger discourse that claimed

The Tokyo police played a major role in administering the State’s increasing interest in the control and oversight of the body.

In a society where the body is increasingly the site of political and social control, it also becomes the essential tool for opposition.

One of the students who was injured in a confrontation with the police during the antitreaty protests expressed his desire that the wound last the rest of his life in order to inscribe his political experiences as a physical scar.1

The artists that eventually formed the NeoDada group were deeply influenced by this contestation and violence of the body. In fact, the NeoDada's manifesto was read aloud at the demonstrations, saying that "the only way to avoid being butchered is to become butchers ourselves.

Performed as provocative responses to the era’s political climate, the neodada art actions were meant to shock and interrupt the everyday spaces of Tokyo in order to demonstrate how bodies were being increasingly obstructed, sterilized, and surveilled through Tokyo’s path to modernity.

Performed as provocative responses to the era’s political climate, the neodada art actions were meant to shock and interrupt the everyday spaces of Tokyo in order to demonstrate how bodies were being increasingly obstructed, sterilized, and surveilled through Tokyo’s path to modernity.

Performed as provocative responses to the era’s political climate, the neodada art actions were meant to shock and interrupt the everyday spaces of Tokyo in order to demonstrate how bodies were being increasingly obstructed, sterilized, and surveilled through Tokyo’s path to modernity.

Performed as provocative responses to the era’s political climate, the neodada art actions were meant to shock and interrupt the everyday spaces of Tokyo in order to demonstrate how bodies were being increasingly obstructed, sterilized, and surveilled through Tokyo’s path to modernity.

The crowd congregated with a collective belief, sought for mutual supports, and demanded to express their discontent with the dictatorial politics. They stood hand-in-hand and clashed head-on with the police using their body as the medium for political expression. In this way the living body—as both the user and producer—endowed the space with new social order while also creating new space through the appropriation of the built environment.