Japanese urban planning, characterized by a high degree of centralization and administrative power of the central government, was also heavily influenced by the modern planning practices ideas taking place in Western towns and cities (Sorensen). Broad avenues, large parks, green corridors, and stunning architecture were seen as symbols of progress.

However, when news arrived in 1959 that Japan’s capital city had been chosen to host the 1964 Olympic Games, the municipal government chased bold new architecture and public works projects in order to present a new, beautiful, and modern Tokyo to the world. Numerous plans were proposed, creating an architectural debate obsessed with aesthetics and industrial architecture, as well as pride and enthusiasm in economic growth.

After being nearly destroyed in WWII, the postwar reconstruction of Tokyo ushered in a highgrowth economy that quickly transformed the city into a modern metropolis. Large redevelopment projects were planned in order to create a modern State that could compete with the cities of the West.

Violence of the City

The squalor and decay unfolding in Tokyo’s unplanned residential areas was masked by the sleek facade of Downtown Tokyo’s shopping district, Ginza. This district was the nucleus of the city’s beautification campaign in preparation for the Olympic Games, where the metropolitan police used sought to sanitize the environment and create a “bright and crimefree town”.

There is an inverse relationship between the quality of moral life and the quantity of urban bodies. In the city, “everything is judged by appearance because there is no leisure to examine anything (Rousseau 1960, 59). Citizens become more selfish, more concerned with accumulating wealth and reputation than personal value.

March 1960,

1st exhibition

Ishibashi Yasuyuki. Fifteen-Minutes in Waseda Street in the Morning.

Sept 30, 1960,

Tokyo Gas Hall,

The Bizarre Assembly

September 1960

walk through Ginza district

1960

Shinohara Ushio demonstrated his "box painting" in front of Yoshimura’s atelier in Shinjuku

Sept 1-7, 1960, 3rd exhibition

Yoshimura Masunobu, Shinohara Ushio, and Masuzawa Kinpei in Hibiya Park Action (Hibiya Kōen akushon)

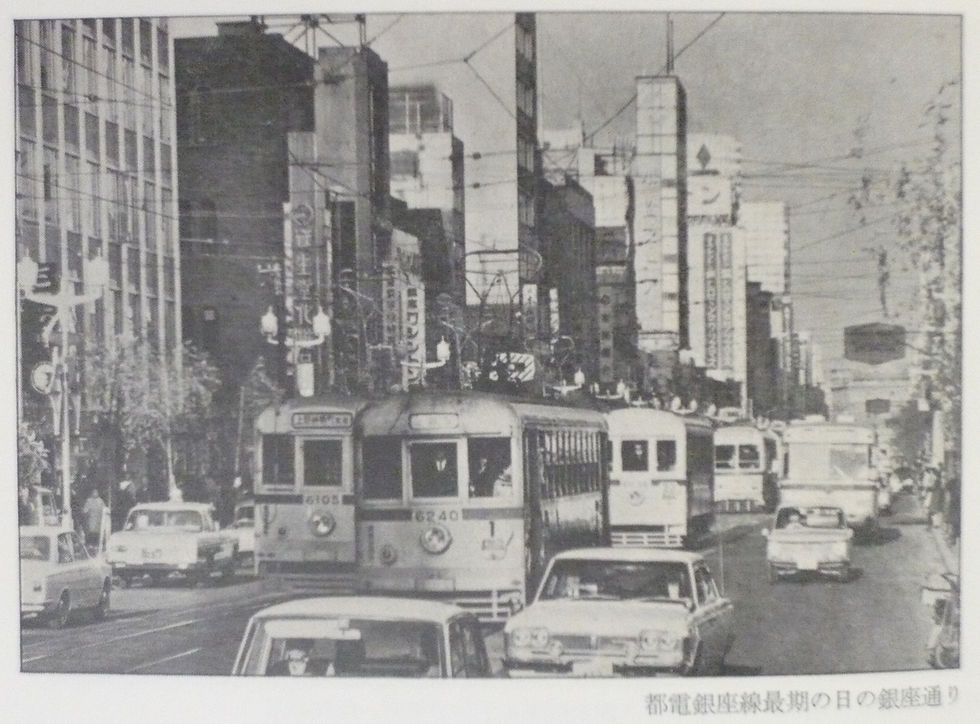

In the mid-50s, most of the districts of Tokyo, including Ginza, were waterfront districts that still relied on river transport. With the economic growth and the development of vehicle-centered transportation, the moats around the Ginza area were filled up and transformed into expressways at the end of the 1950s.

The construction of subway lines followed shortly afterwards. Since the first completion of Ginza station in 1957, several lines and subway stations were opened one after another in the early 1960s.

This urban renovation tremendously changed the cityscape—both spatially and socially—and created an iconic image of Ginza: the interweaving flow of crowds, motor traffic, and flickering neon signs.

The NeoDada artists opposed what they saw as a perversion of urban space, and placed their performances within Ginza in order to expose its hidden logic as an environment for social control. It’s ritual order, and the hedonistic fascination with modernity it inspired in the public, is instead seen as a mode by which the State regulates culture and everyday life in Japan.

Motorized traffic eventually led to the shutdown of the trams in 1967, which at the time had busily shuttled passengers throughout the city.

While images of large Tokyo shopping streets overflowing with pedestrians have become a popular representation of the city, at the time this transformation of everyday life implied a violence of the city on human behavior. If seen as a kind of stage, the ritual order of these modern spaces “is precarious and in need of constant repair...order exists insofar as social actors seek to avoid stigmatization and embarrassment in public gatherings.”

The crowd congregated with a collective belief, sought for mutual supports, and demanded to express their discontent with the dictatorial politics. They stood hand-in-hand and clashed head-on with the police using their body as the medium for political expression. In this way the living body—as both the user and producer—endowed the space with new social order while also creating new space through the appropriation of the built environment.